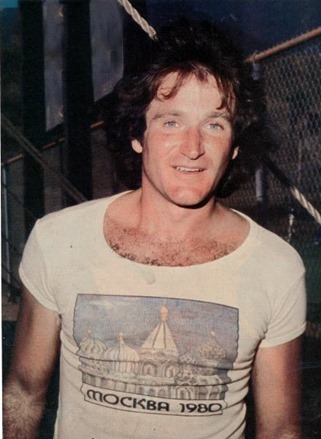

I wish I could express how profoundly sad I am about the loss of Robin Williams. As a comedian, he was a genius, with a mind that seemed to burn at a temperature mere mortals could never have tolerated. As an actor, he was sensitive, empathetic, and almost disturbingly honest. Losing the brilliance of his talent is tragic.

As someone who suffers with mental illness and severe, sometimes suicidal depression, he was family. A brother. A hero — and a very sick man who lost his battle with mental illness in the most devastating way possible. He will be remembered for the joy he brought to the world, the massive body of work he left for us, the cavernous paths he carved in so many different artistic mediums, and, most of all, for the complex and delicate humanity he brought to an industry that works so hard to be beyond human.

One of the things that made Robin Williams remarkable was how accessible he was about his demons. It was no secret that he suffered from depression, was bipolar and struggled with substance abuse for most of his life. His trips in and out of rehab were public knowledge, and he spoke openly about taking life one day at a time, and celebrating the small victories. The fact that those internal opposing forces ultimately won is too painful to even contemplate right now.

I am absolutely heartbroken.

I wrote this letter to comedian Paul Gilmartin about a year and a half ago. He hosts a regular podcast called The Mental Illness Happy Hour and explores all aspects of mental illness, from all perspectives. It’s often quite insightful and occasionally gut wrenchingly heartbreaking. I wasn’t going to make this letter public, for the reasons I explain in the letter itself, but recent events have made me reconsider.

Comedian Jimmy Pardo (who was one of the subjects of this letter) posted about Robin Williams on his Facebook tonight, and (as so often is the case) some hideous creature decided to post an heartless and ignorant comment about people who take their own lives. It was the first comment on the post. The second comment was from Jimmy’s wife, Danielle Koenig, whose brother was lost to suicide. It was infuriatingly cruel and made me want to express to Jimmy and Danielle exactly the sentiments that are in this letter. Which is why I’m publishing it now. I never sent it to the people I wanted to send it to, because I was worried about needlessly agitating painful and raw wounds. Seeing that comment though, reminded me that those wounds will always be raw and always be painful, and maybe the benefit of my perspective might outweigh the consequences of sharing it. Either way, I’m sharing it now. I don’t know if Jimmy or Danielle, or any of the people affected by the loss of Andrew Koenig will ever see this, and I’m okay with that. I do feel like my experience in that tragedy is worth sharing.

Here is that letter, dated December 3, 2012:

Hello Paul,

I’m writing to you because I can’t write to the person I really want to because it would be inappropriate and awkward, and probably needlessly cruel. I’m writing to you because you know at least one or two of the parties involved and because I trust you will understand why I’m writing it to you instead of them. I have been predisposed to suicidal impulses for the majority of my life. I attempted suicide in the fourth grade and it was an ongoing theme in my life well into adulthood. Without getting into all the whys and hows of my history that destroyed certain elements of my self-worth and mental stability, I’ll just say that I come from a chaotic, broken household with various forms of abuse.

Things really came to a head when I was in my late twenties. I was married (still am) and stuck living in a place I hated and without the means to escape. I made up my mind to finally really kill myself and I sat my wife down and tried to explain to her all the reasons why she, and the rest of the world, would be better off without me. Obviously this didn’t go well and I ended up in a mental hospital. I got medicated and pulled far enough from the edge that I wasn’t in constant danger, but I was far from healthy.

Sorry if I’m running long here. I just feel like I need to provide some context.

For the next few years I continued to live with the constant low resonating hum of suicide vibrating in the pit of my stomach like the bass line from some ominous song, threatening to crank up the volume at any moment. It was my go-to response to pretty much any stress or unhappy situation. If anything distressing happened, I would immediately begin planning my own death. Sometimes it was purely in my head, sometimes it involved vocalizing it to people I cared about. No one would have been surprised if I had killed myself.

Now, for the reason I’m writing to you. I listen to a lot of podcasts. I’m quite interested in comedy (as a fan and as a writer) and I’m fascinated by the lives of the people who perform and create comedy. I’m a big fan of WTF and Comedy Death Ray (or Bang Bang they’re calling it now) and Never Not Funny. It was Never Not Funny that actually changed my life. As you know, Andrew Koenig was an active participant on Never Not Funny, both as the video engineer and as on-air talent. Listening to the podcast, and watching the news about Andrew’s death (I live in Victoria BC, across the water from Vancouver where Andrew died, and it was on the local news a bit here. I don’t know how much it was covered nationally) affected me profoundly. Specifically listening to the episodes of NNF after Andrew’s death. I cried watching his father give the statement that Andrew had died. I cried listening to Jimmy and Matt talk about Andrew in the episodes that followed. It fundamentally changed the way I view suicide and what it does to people.

I tended to think of suicide as a kind of “rip the band-aid off” scenario. I understood that it would be painful for a few people, but that ultimately it would be for the better. I believed that whatever pain people might have felt over my death would be outweighed by the relief they would feel from no longer having to carry my baggage. I don’t know what internal ghosts were haunting Andrew, and I don’t presume to understand what was going on in his head or heart. I do, however, understand what it feels like to have the volume on that background noise turned up so loud that you can’t hear anything other than the thud-thud-thud of “YOU HAVE TO DIE” beating into your brain. Even if people are screaming for your attention, if the volume is loud enough, you can’t hear them. Listening to the drama of Andrew’s death play out both on the news and on NNF made me realize that suicide isn’t relieving anyone of anything. It’s a hand-grenade tossed into a room full of the people you care most about. I don’t get angry at people who commit suicide, and it infuriates me when people call it weak or cowardly, but I do now find it horrific and immensely sad. The most shocking thing to me is that I now also find the thought of my own suicide horrific and immensely sad.

After Andrew died, I decided that I would never, ever do that. Not just because of the damage it would do to the people who care about me (there aren’t many, but enough) but also because I now find it fundamentally wrong, in a very deep, almost spiritual way. I don’t believe in god, but I do believe that every human being alive on earth has a spark inside of them. A fire that can generate warmth and energy and sustain life, and that can burn down an entire town when not tended properly. That spark is the most important thing about a person and I find it fundamentally evil to snuff out that spark, in another person or in myself. So even when I hate myself (which I often do) I feel the need to protect that spark inside of me, and inside of others.

So I’m writing to you because I can’t write to Jimmy Pardo or Walter Koenig or Danielle Koenig. I can’t tell them that Andrew’s death probably saved my life. That even though they suffered the worst kind of loss a person can suffer, the few people who care about me and want me to live won’t ever have to go through that. At least not because of me. I can’t tell them that Andrew’s death has made me a more compassionate person, both to myself and to other people suffering with depression and other forms of mental illness. I wish there was a way I could tell them, especially Jimmy (because it was his show and the voicing of his grief that most impacted me) that I’m truly sorry for their loss, but that through that loss, at least one life will carry on when it likely wouldn’t have otherwise.

By this point, I’ve spent hundreds of hours listening to Jimmy Pardo’s voice through his podcast. I know thousands of tiny, personal details about his life, shared through that show. Funny, absurd, heart breaking, infuriating… all played out in my headphones. There’s this one-sided deeply intimate relationship developed there that makes me desperately want to express my thanks and heartfelt gratitude for allowing the pain and horror of Andrew’s death play out through the podcast. Jimmy and Matt opened their hearts in an incredibly vulnerable and honest way that changed my life forever. But I can’t tell them that. I can’t think of a way to express any of this to them without feeling like a complete asshole. It’s impossible to explain how I can be thankful for the way they shared the pain of Andrew’s death without sounding like I’ve benefited from Andrew’s death. I don’t know how to do it.

So I’m writing to you, Paul. Because I believe you when you tell me that I’m not alone. I’ve been sitting on this for a couple years now, unsure who to tell and exactly what I was feeling. I keep getting swells in my chest that are either impending tears or a panic attack as I write this. Even though I can’t express this to the people I want to express this too, I feel like by telling it all to you, and you will carry my gratitude inside you the next time you talk to Jimmy or Matt or Danielle, and that will be enough for me. There’s an intense sense of fear and nervousness as I get ready to send this to you. I trust you though, and I hope this wasn’t too long-winded or rambling or just plain stupid. It’s something I’ve needed to say for a very long time and I’ve never had anyone to say it to until now. I sent Marc Maron some artwork a while ago and tried to put some of these thoughts together, but I wasn’t really ready to say what I needed to say, and he wasn’t really the guy who I needed to say it to. So thank you as well. This has helped me.

Thank you for the show and thank you for sharing with us. You do good work and it is appreciated.

Joe

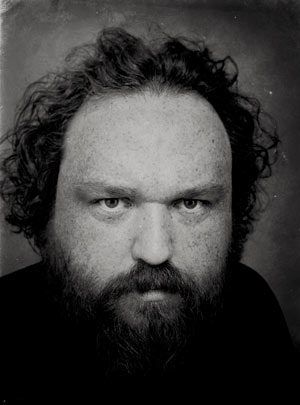

Joe Humphrey is an American writer living in Canada. Bloodletting is a passion project in development for over fifteen years. His selfie game is strong.

Joe Humphrey is an American writer living in Canada. Bloodletting is a passion project in development for over fifteen years. His selfie game is strong.